These are the prefaces from the Oxford science dictionaries. I hope they will be useful to fellow lifelong learners in choosing a science reference book.

Oxford Dictionary of Biology Preface

This dictionary was originally derived from the Concise Science Dictionary, first published by oxford university press in 1984 (fourth edition, 1999, retitled A Dictionary Of Science). It consisted of all the entries relating to biology and biochemistry in this dictionary, together with those entries relating to geology that are required for an understanding of paleontology and soil science and a few entries relating to physics and chemistry that are required for an understanding of the physical and chemical aspects of biology (including laboratory techniques for analyzing biological material). It also included a selection of the words used in medicine and paleoanthropology.

Subsequent editions saw the addition of more terms relating to human biology, environmental science, biotechnology and genetic engineering, and food technology (among other fields), as well as a number of short biographical entries on the biologists and other scientists who have been responsible for the development of the subject, the inclusion of several chronologies tracing the history of some key areas in biology, and a few two-page feature articles on selected topics.

For this edition many entries have been substantially updated and over 300 new entries have been added in all the major fields. The coverage of cell biology and molecular genetics, in particular, have been greatly expanded, reflecting recent advances in these rapidly developing areas, and two new Appendices have been included.

An asterisk placed before a word used in an entry indicates that this word can be looked up in the dictionary and will provide further explanation or clarification. However, not every word that appears in the dictionary has an asterisk placed before it. Some entries simply refer the reader to another entry, indicating either that they are synonyms or abbreviations or that they are most conveniently explained in one of the dictionary’s longer articles or features. Synonyms and abbreviations are usually placed within brackets immediately after the headword. Terms that are explained within an entry are highlighted by being printed in italic type.

The more chemical aspects of biochemistry and the chemistry itself will be found in A Dictionary Of Chemistry; this and A Dictionary Of Physics are companion volumes to this dictionary. SI units are used throughout this book and its companion volumes.

Oxford Dictionary of Chemistry Preface

This dictionary was originally derived from the Concise Science Dictionary, first published by oxford university press in 1984 (fourth edition, retitled A Dictionary Of Science, 1999). It consisted of all the entries relating to chemistry in this dictionary, including physical chemistry, as well as many of the terms used in biochemistry.

Subsequent editions included special feature articles on important topics as well as several chronologies tracing the history of some topics and short biographical entries on the chemists and other scientists who have been responsible for the development of the subject.

For this fifth edition the text has been revised, some entries have been substantially expanded, and over 160 new entries have been added covering all branches of the subject.

An asterisk placed before a word used in an entry indicates that this word can be looked up in the dictionary and will provide further explanation or clarification. However, not every word that appears in the dictionary has an asterisk placed before it. Some entries simply refer the reader to another entry, indicating either that they are synonyms or abbreviations or that they are most conveniently explained in one of the dictionary’s longer articles or features. Synonyms and abbreviations are usually placed within brackets immediately after the headword. Terms that are explained within an entry are highlighted by being printed in italic type.

The more physical aspects of physical chemistry and the physics itself will be found in A Dictionary Of Physics, which is a companion volume to this dictionary. A Dictionary Of Biology contains a more thorough coverage of the biophysical and biochemical entries from the Dictionary of Science together with the entries relating to biology. SI units are used throughout this book and its companion volumes.

Oxford Dictionary of Physics Preface

This dictionary was originally derived from the Concise Science Dictionary, first published by oxford university press in 1984 (fourth edition, retitled A Dictionary Of Science, 2005). It consisted of all the entries relating to physics in the Concise Science Dictionary, together with those entries relating to astronomy that are required for an understanding of astrophysics and many entries that relate to physical chemistry. It also included a selection of the words used in mathematics that are relevant to physics, as well as the key words in metal science, computing, and electronics.

Subsequent editions have been expanded by the addition of many more entries, including short biographies of important physical scientists; several chronologies tracing the history of some of the key areas in physics; and a number of special one- or two-page feature articles on important topics.

For this fifth edition the text has been revised, many entries have been expanded, and over 200 new entries have been added covering all branches of the subject.

The more chemical aspects of physical chemistry and the chemistry itself will be found in A Dictionary Of Chemistry; and biological aspects of biophysics are more fully covered in A Dictionary Of Biology, which are companion volumes to this dictionary.

An asterisk placed before a word used in an entry indicates that this word can be looked up in the dictionary and will provide further explanation or clarification. However, not every word that appears in the dictionary has an asterisk placed before it. Some entries simply refer the reader to another entry, indicating either that they are synonyms or abbreviations or that they are most conveniently explained in one of the dictionary’s longer articles or features. Synonyms and abbreviations are usually placed within brackets immediately after the headword. Terms that are explained within an entry are highlighted by being printed in boldface type. SI units are used throughout this book and its companion volumes.

Oxford Dictionary of Science Preface

This fifth edition of A Dictionary of Science, like its predecessors, aims to provide school and first-year university students with accurate explanations of any unfamiliar words they might come across in the course of their studies, in their own or adjacent disciplines. For example, students of the physical sciences will find all they are likely to need to know about the life sciences, and vice versa. The dictionary is also designed to provide non- scientists with a useful reference source to explain the scientific terms that they may encounter in their work or in their general reading.

At this level the dictionary provides full coverage of terms, concepts, and laws relating to physics, chemistry, biology, biochemistry, paleontology, and the earth sciences. There is also coverage of key terms in astronomy, cosmology, mathematics, biotechnology, and computer technology. In addition, the dictionary includes:

• over 160 short biographical entries on the most important scientists in the history of the subject

• ten features (each of one or two pages) on concepts of special significance in modern science

• ten chronologies showing the development of selected concepts, fields of study, and industries

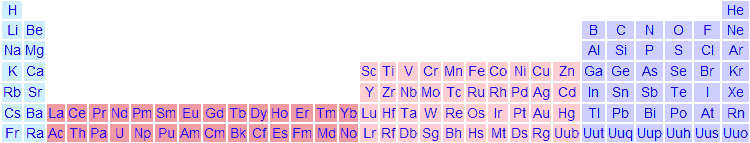

• eight Appendices, including the periodic table, tables of SI units and conversion tables to and from other systems of units, summary classifications of the plant and animal kingdoms, and useful websites.

For this fifth edition, over 300 new entries have been added to the text, incorporating recent advances in all the major fields and increased coverage of climatology, seismology, and computing.

In compiling the dictionary, the contributors and editors have made every effort to make the entries as concise and comprehensible as possible, always bearing in mind the needs of the readers. Particular features of the book are its lack of unnecessary scientific jargon and its extensive network of cross-references. An asterisk placed before a word used in an entry indicates that this word can be looked up in the dictionary and will provide further explanation or clarification. However, not every word that is defined in the dictionary has an asterisk placed before it when it is used in an entry. Some entries simply refer the reader to another entry, indicating either that they are synonyms or abbreviations or that they are most conveniently explained in one of the dictionary’s longer articles. Synonyms and abbreviations are usually placed within brackets immediately after the headword. Terms that are explained within an entry are highlighted by being printed in boldface type. Where appropriate, the entries have been supplemented by fully labelled line-drawings or tables in situ.